Crimes and Misdemeanors: What I Did To Find My Birth Parents

What I did in my journey as an adoptee starts at the beginning of my life. I was born in a car, dropped off at a hospital, handed over to “The Agency,” and adopted at 2 months of age. My childhood was less than ideal. My adoptive mom committed suicide; my adopted brother died in an auto accident, and my adoptive father was verbally abusive—telling me on the day following my brother’s death that I should have “died instead of him” since I was “the bad child.”

I hoped someday to meet my biological family and periodically mentioned this to Dad. His response was always swift and assaultive: “You can’t find those people. The records were destroyed.” Although I questioned his honesty, I visualized my files in flames and a tractor turning “The Agency” into rubble.

When I hit my mid-20s, I vowed to track down my biological parents, assuming my records were still intact. I faced a posse of naysayers. “You can’t do it!” “Don’t waste your time!” “My niece spent five years and five thousand dollars trying to find her family—all for nothing!” An “agency” employee explained over the phone that Georgia law prohibited providing “real names” to adoptees.

Records are still closed in my home state of Georgia, and they are sealed or partially sealed in 40 others, making it difficult for the five million adoptees in the U.S. to learn about their roots. Thankfully, there are websites today that can provide valuable advice, such as Adoption.com. Plus, there are adoptee registries, DNA testing services, and professional adoption researchers; they can aid with the search.

These resources did not exist for me back in 1984, so I contacted the front desk of the Atlanta hospital where I had been born, hoping to acquire the names of the little girls born on my birth date. I was rebuffed, so I did what a persistent adoptee would do: I turned to crime. Actually, I embarked upon a potential misdemeanor by acting as if I had authority (*Adoption.com does not endorse doing this; all views expressed in this blog post are the author’s and do not represent the opinions of Adoption.com). I telephoned the hospital’s records department and forcefully asked for the information. I said, “I need the names of the baby girls born on May 11, 1960.” Somehow, I was convincing. I sounded important. I was given four names.

I stared at the names, digging into the bowels of my being, and decided that “Rachelle Wilpan” must be my first name. There was no logic to this decision; it was pure intuition. My next step was to confirm my hunch with “The Agency” because I had no interest in spending time, money, and precious perseverance tracking down the wrong folks. Plus, I did not want to throw a bunch of strangers’ lives into turmoil if they were not related to me.

I met with a lady from “The Agency” whose office was filled with baby photos; they were affixed to walls and crammed onto tables and bookshelves. I wondered if my “mug shot”—my chubby, little cheeks from 1960—were among the lot. Baby Lady explained that by revealing my parents’ names, we would be committing a felony, subject to criminal and civil penalties. “It could land us both in jail,” she said. “I can’t be part of something like that.”

It was time to whip out my trump card. “Could Rachelle Wilpan be my real name?” I asked. I figured this question would elicit a definitive response. Either Baby Lady would confirm that I was right (if only by her facial expression), or she would say “no” because she would not want me to contact the wrong people, thus embroiling “The Agency” in a mess.

Baby Lady became flustered, frazzled, and fidgety. She glanced around the room as if seeking advice from her menagerie of tiny tots. Then she did something truly unexpected: she invited me to conspire in a crime. “I’m going to leave the file open on my desk with the names on top,” Baby Lady said. “I will be gone for exactly ten minutes. You will be in this office alone. Do you understand?”

I smiled and nodded, fully prepared to do a ski jump over the law and elevate my status from Misdemeanor Mary to Felony Fran. Baby Lady departed, and I studied the file, jotting down names, locations, and other crucial data. Although my last name was not “Wilpan,” it was so incredibly close that I made a toast to intuition. (I later learned that my first name had not been in the hospital records because my mom had given birth through the free clinic.)

The adoption file stated that my birth father was studying to be a Baptist minister, and I knew Emory University in Atlanta had a top-rated seminary program. So I contacted their alumni association, and pronto, I got his phone number. When I called, he was shocked and understandably guarded—but also emotional—informing me that he had been a “partial person, walking with a limp” because he never knew where his daughter might be. He agreed to meet with me two weeks later in his hometown.

I waited in an anteroom at the university where my birth father worked as a professor. He had agreed to meet me following a faculty meeting. I was nervous; I picked at my nail polish, twirled my pinky ring, and crossed my legs to the left, then to the right, and back to the left. Would the professor be tall or short, outgoing or introverted, receptive or rejecting? Would he greet me with a hug or say, “Nice to meet you, kid” and send me away?

Suddenly, a door opened, and dozens of faculty members poured into the anteroom. I intuitively knew which one was my birth father. He was of average height, had blue eyes, and a handsome, friendly face. He wore a red, plaid tie and business suit. He invited me to join him for lunch at the campus cafeteria. He had authored academic books and had lived abroad; he enjoyed philosophy and history. He was open-minded, introspective, and soft-spoken. I immediately felt great respect.

The professor had met my mother at church, and they’d started dating. Then she got pregnant, and they married but with plans to divorce after placing me for adoption. “I think she was trying to trap me by getting pregnant,” he added. Frankly, I doubted this was the case as the “trapped feeling” is fairly common among single men facing fatherhood. The professor prearranged my adoption, and my birth mom went along with his decision. This would have made no sense if she’d been trying to manipulate him.

“You were born in the backseat of the car. I was driving. Your mother was in labor for 15 minutes.” He sounded uneasy just mentioning it. I could imagine him as more emotional and tense than most new dads, although outwardly restrained. “They took you out of the car at the hospital, and we never saw you again.”

“Why did you divorce?” I asked. He explained that the relationship could not last due to an ideological disconnect. He was a traditionalist, while my mom was postmodern. He was a red state, while my mom was a blue one. He was deeply Christian, while my mom was agnostic with a leaning towards Unitarianism and Reform Judaism.

Despite the often-strained accounts of my birth parents’ rocky relationship, my two-day visit with the professor was not strained or rocky. It was delightful. I audited his classes. We enjoyed several meals together, and I learned about his life. He also played tour guide, showing me the attractions around campus. This visit with the professor marked the beginning of a lasting bond between us—one of regular communication via letters, emails, and phone calls.

My birth mother, on the other hand, was the “Where’s Waldo?” of my life. She was so elusive that I began to think she was part of the witness protection program. Two days of searching turned into two months which turned into two years. I phoned county libraries and asked clerks to sift through phone books for residents with her last name. I spoke to her graduating university; they provided me with an outdated address. I questioned her previous neighbors and former classmates. No one knew her whereabouts, but many strangers were supportive and offered to thumb through local records and make inquiries themselves. I had an army of amateur detectives on the East Coast helping me with my mission. I even stumbled upon some biological cousins; they admitted that my mom had vanished years ago. “Poof. Gone,” one said. “No one knows where she is.”

Eventually, I focused on high school because my grandmother had been a teacher. And that is when I finally did the adoptee’s victory dance. An office assistant at Towson High was in touch with my aunt, who was in touch with my mom, who was eager to be in touch with me. After a flurry of phone calls, all was arranged for a meet-and-greet at my grandmother’s house in Florida.

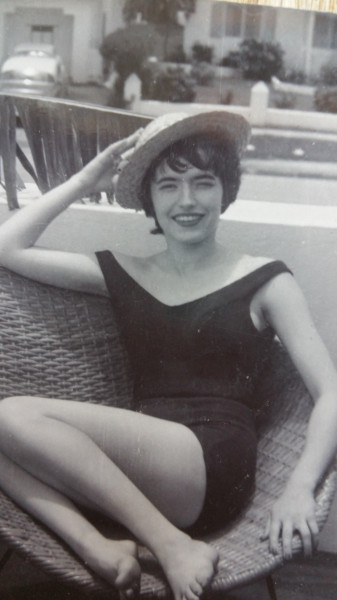

The big day arrived, and I flew to Florida. I was welcomed by two aunts, my grandma, a cousin, and my birth mom. One aunt was athletic; she taught aerobics. The other aunt was a homemaker and a talented cook. My teenage cousin had a corkscrew hairdo that looked like an explosion of Rotini pasta. My eccentric grandma flaunted the color fuchsia—from her Scarlett O’Hara hat all the way down to her long dress, stockings, and hot pink shoes. She also had an impressive color-coordinated closet. My birth mother, Sharon, was pretty and thin and brown eyes and shoulder-length brown hair. She looked like Elizabeth Taylor in the 1958 film Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. She was an environmentalist and enjoyed camping, gardening, and canoeing when not working as a social worker in Washington, D.C.

Sharon gave me her version of events. She and my birth dad had dated during college, but they had little money. They could not afford fancy restaurants, the theater, or pricey dance clubs. The professor tinkered with his 20-year-old vehicle to keep it running, diluted his grape juice with water to save money and enjoyed finding underpriced books and other keepsakes at thrift shops around town. “I’ll put this vacuum cleaner together to see if it works,” Sharon told him one afternoon at the Salvation Army. “No,” he replied. “I want to get it for five bucks. I don’t want them to think it works.” Afterward, they rode the streetcar back to his one-room apartment with the five-dollar Hoover.

Sharon told me that when she got pregnant, my birth dad’s world crumbled. He felt shame. He had committed what he viewed as an unpardonable sin: engaging in premarital sex. He not only chastised himself, but he also feared the outside world would learn about his moral and religious failings. They were the anchors of his life, his most treasured possessions. They had meaning for him just as fancy dresses had meaning for my grandmother. The professor felt that losing his grasp on these absolutes would leave him in a void, in shreds, in a subjective and relative world without God. To his mind, there was only one solution: to distance himself from his child via adoption and to distance himself from his wife via divorce. He hoped these measures would permit him to retain a sense of self and begin anew.

Sharon returned to college in Maryland to complete her bachelor’s degree. She and the professor talked on the phone regularly; he was in emotional pain and suggested getting back together. But she felt it was too late. Their baby was gone, and the two of them could no longer build castles in the sand. Their relationship had become an ever-dimming light—murky, helpless, and broken. Sharon eventually remarried but had no other children, which might partly explain why she so quickly embraced me as a part of her life.

Today, I have my own menagerie, not of baby photos, but treasured biological kin. I meet with them regularly, speak with them on the phone, swap letters and text messages, and exchange holiday gifts. In other words, we do what other families do.

And thankfully, I no longer suffer the pain of being in the dark about my roots while enduring the hollowness of pretending I am not. I no longer ponder the question of “Who am I?” while mourning for the family I have never known. I am no longer consumed by internal angst as well as the external battle to uncover the truth. The mystery is finally solved.

I am at peace.