Mirror, Mirror | Creative Parenting

Finding creative ways to communicate with a child is challenging under the best circumstances.

Dealing with a child who has the gift and burden of autism provides additional opportunities for divergent thinking. Layers of trauma, PTSD, and ADHD bring an even greater need for invention.

National Institutes of Health documents studies showing children with traumatic beginnings may have more difficulty with new learning.

As parents or caregivers of foster and adopted children, we mustn’t discount the effect early trauma, separation, and neglect reek on brain development. Although it is sometimes difficult to determine whether the learning difficulty is organic or contrived by the child to meet a felt need for attention, we have to find creative ways to communicate clearly.

Our daughter exhibits Reactive Attachment Disorder. Our son is on the Autism Spectrum and has PTSD. Both are diagnosed with ADHD, although I often wonder whether the attention issues will minimize once they’ve been able to more effectively deal with their past trauma.

Both of our adopted children struggle to understand abstract concepts, so my husband and I look for ways to help them understand in concrete terms.

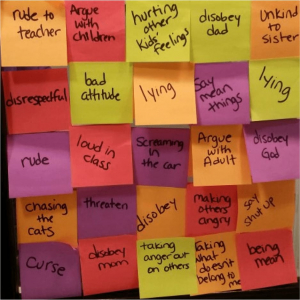

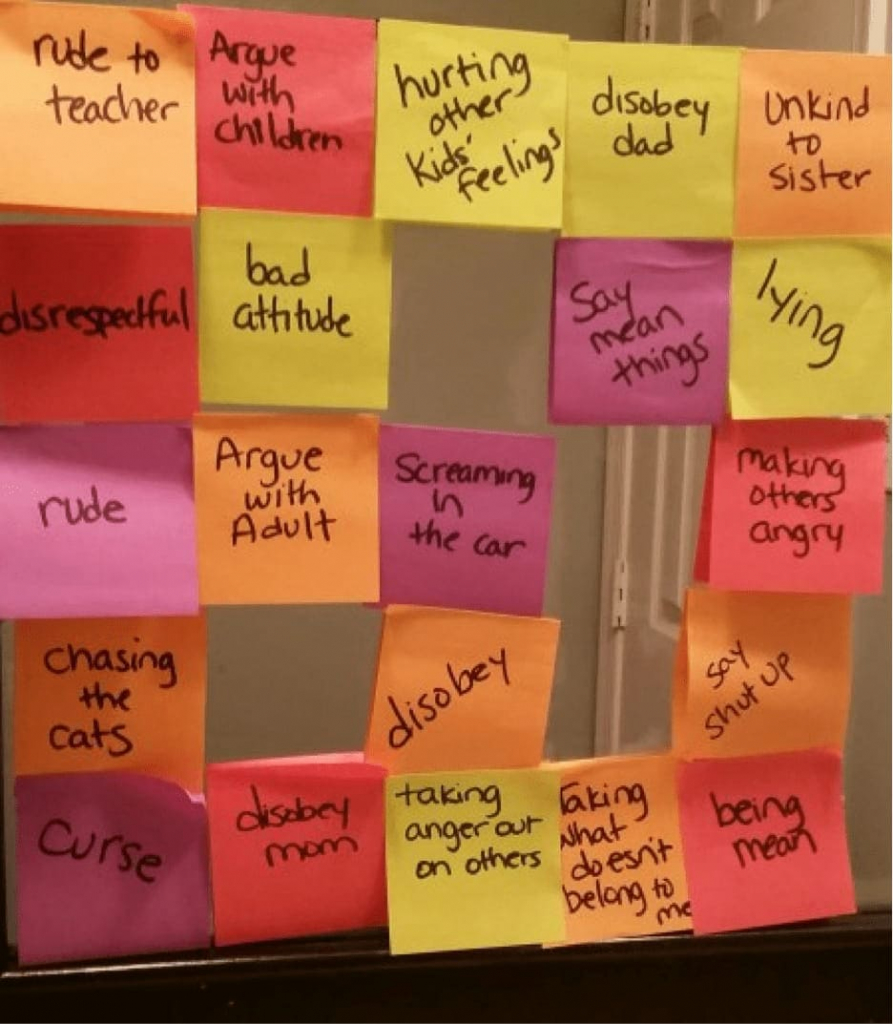

During a recent discussion with our son about how his negative behaviors prevent people from seeing him, his inability to grasp the nebulous idea frustrated us both.

A stack of sticky notes caught my eye.

“Hey, Buddy, let’s make a list of the behaviors you struggle with controlling.”

I watched his face, wondering if the exercise would upset him. Instead, he seemed to relish making the list as long as possible. As he ticked off troublesome behaviors, I wrote each on a sticky note.

Taking the stack of notes into the bathroom, I arranged them in a large square on the mirror and then called him to see the colorful masterpiece.

“What do you see?”

He stared at the mirror, and again I wondered whether this might be overwhelming. We always walk the line of being psychologically open and honest without being hurtful. Would it be too much, seeing this many negative behaviors in one place?

Squinting at the block of words, he said, “I see bad behavior.”

I started to remove notes.

“Tell me when you start seeing the boy.”

When I pulled away the fourth square, he yelled, “I see me!”

He looked again, repeating, “I can see me.”

Still not sure he’d make the connection, but hoping, I said, “Tell me what this means.”

Considering for a moment, he said, “When my behavior is mean, it’s so big that people can’t see around it or through it. I am still here, standing behind it, but all they see is what I do, and they don’t like what I do. So I think they don’t like me. But if I take away the bad behavior, people can start to see me, and maybe they will like that boy.”

Sometimes I am amazed at his thought process.

And then he completely blew me away.

“Can we leave all of them on the mirror? And then, every day when I do something good, I can take one off. And then, after a couple weeks, they’ll be all gone.”

It hasn’t solved the entire problem; every day brings new challenges. However, the concrete example helped him understand why he gets the vibe people don’t like him when he’s misbehaving. They don’t dislike him; the angst is directed at his behavior. When he removes or diminishes the behavior, the negative feelings decrease or go away altogether.

Understanding the concept doesn’t mean he’ll be able to effectively apply it, but we’re getting there. Helping the brain recover from trauma, one step at a time, is the long term goal.

If your child is struggling to recover from trauma (or even if they’re just stubborn), try finding creative ways to convey abstract concepts. Even if they don’t seem to understand fully, taking time to find ways to communicate shows how much you care.

Especially for kids who’ve experienced separation, abandonment or trauma, knowing someone cares enough to make the effort to connect will ultimately make a difference. Not immediately, of course, but we’re in this for the long game.

Because we can see the kids behind the behavior.