My Journey Through Post-Adoption Depression

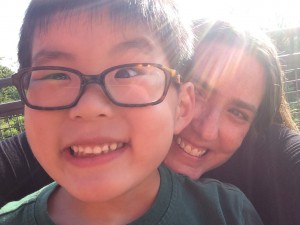

I’m someone who wears her heart right out there on her sleeve. And, as a happily married mom of a now-8-year old son from South Korea, I openly discuss my journey through the world of post-adoption depression. I’m willing to talk about it with anyone willing to listen.

But it wasn’t always that way.

Even for someone like me—who is super comfortable talking about my life, my emotions, my family, my feelings—it took years for me to be comfortable admitting to myself, much less revealing to others, that I suffered from post-adoption depression. It happened very shortly after my son came home to us from South Korea through international adoption.

Post-adoption depression remains a mystery to many. In fact, many have never even heard of it. Adoption agencies do their best to address it in pre-adoption prep seminars and waiting parent support group meetings. But, even then, it’s often only mildly touched on—and not explained in enough detail to make parents realize that they may actually experience it someday themselves.

That’s why I continue to write about it, and my personal experience with it. Many parents don’t tell anyone what they are going through. They deny the depression they’re feeling—for so many reasons. We who have shared their journey need to let those parents know: They are far from alone. By dealing with their depression, and seeking the help they need, they and their families will be okay.

How do I know? Because, now, I’m okay. But, for a while, I wasn’t. My story begins in 2006.

A Child is Born

In 2006, after years of infertility, my husband and I learned that our first and only course of IVF had actually worked: I was pregnant! But, our pregnancy bliss abruptly ended one day, a few months later, when I experienced what is known as preterm premature rupture of the membrane (pPROM). In layperson terms, my water broke—way, way too early. After months of a relatively drama-free pregnancy, we ended up at the hospital for a full week, desperately trying to get my fluid levels back up so the baby could survive.

In 2006, after years of infertility, my husband and I learned that our first and only course of IVF had actually worked: I was pregnant! But, our pregnancy bliss abruptly ended one day, a few months later, when I experienced what is known as preterm premature rupture of the membrane (pPROM). In layperson terms, my water broke—way, way too early. After months of a relatively drama-free pregnancy, we ended up at the hospital for a full week, desperately trying to get my fluid levels back up so the baby could survive.

He did not.

We endured a heartbreaking miscarriage of my son Christopher at 18½ weeks. I was far enough along where I had to actually give birth to my son—even though I knew the outcome. Our journey of hope and pregnancy ended with full labor and delivery, and a simultaneous hello and good-bye.

We met our tiny son Christopher Michael, who was soft and silent and still. They brought us holy water, and we baptized him and named him ourselves, quietly saying hello and good-bye to him all in the same breath, in a darkened hospital room in the wee hours of the morning. The songbirds hadn’t even stirred yet to greet the day, and here we were, saying good-bye to our son.

It was the beginning of years of depression for me. I had suffered from depression during our years of trying to form a family, but this was a different kind of depression. Since then, I have gone through years of therapy, discussing the classic “why me” issues and revisiting (and addressing head-on) the trauma of being in that mother-baby ward for a full week.

After it was all over, I remember being wheeled out to the car with a tiny box in my arms. A box of mementos: The clothes the nurses had dressed him in. The tiny little hat. A small photo. The copies of the forms we signed, allowing his body to be transported to the funeral home for cremation. This little box on my lap was the only proof that my son had ever existed.

Creating Our Family Through Adoption

But parenthood came to us in other miraculous ways. After taking a few years to get ourselves together, our lives were blessed deeply by international adoption in 2009. After a long wait, our son, Matthew, came home to us from South Korea in December at age 9.5 months. We couldn’t have been happier. We were parents, at long last!

But parenthood came to us in other miraculous ways. After taking a few years to get ourselves together, our lives were blessed deeply by international adoption in 2009. After a long wait, our son, Matthew, came home to us from South Korea in December at age 9.5 months. We couldn’t have been happier. We were parents, at long last!

Shortly after we adopted Matthew, I would tell whoever would listen just how happy I was.

But, the truth was, I wasn’t happy. I was acting as I thought I should—as any new mom of an adopted child logically would. But, in reality, I was severely depressed. I didn’t know it, I didn’t want to admit it, but, I was suffering from post-adoption depression syndrome (PADS). [KH1]

Years have gone by, and my son is now 8 years old. We are such a happy family, and I am a proud mom. Parenthood is one of my greatest joys. Yes, it came at a high cost. Yes, I wish I had identified my depression earlier than I did. It took a lot of looking deep within myself to admit that I was living with PADS. That didn’t make me wrong, or flawed, or not good enough of a mom. It didn’t make me some sort of horrible person.

I needed help—and, eventually, I got it.

If you think you’re going through PADS, I encourage you to seek the help you need. Now. Because you are not alone. And, if you have never even heard of PADS, keep on reading. If you see signs of PADS in yourself, seek help. You can find the happiness you deserve.

Becoming Matthew’s Mom

On a cold December day in 2009, I became Matthew’s mom at the Korea Air gate at Dulles Airport in Northern Virginia. In the tiny hours of the morning, we held our not-so-tiny little man in our arms for the first time and met the boy who became our son. The tears I cried were a relief. Happiness. Closure to a sad past. Opening to a new beginning.

Days later, I started noticing that something didn’t feel right. I told no one. As my husband and I navigated the new world of new parenthood, I felt a consistently deep presence of sadness. I kept it to myself.

We didn’t discuss it outright. Not right away. We were too busy logging Matthew’s sleep schedule, tracking his feedings, making pediatrician appointments and social worker home visits, getting him used to sleep alone in a crib (in Korea, the moms sleep with the child on a mattress on heated floors; very different than in the U.S.), helping him overcome his jet lag and the time difference, and a million other things.

Jeff and I started to talk about it, just between the two of us. We talked ourselves out of it, convincing each other that I was OK, just dealing with kind of a lot. I was probably fine.

Plus, we didn’t want to mess anything up! The social worker was still visiting our home monthly to see for herself how Matthew was progressing and how we, as a family, were bonding and transitioning. We weren’t going to do or say anything to jeopardize that! The official adoption in the U.S. wouldn’t take place until almost a year later. Our worries were vastly unfounded, of course, and legally, all was fine: But, try telling that to nervous new adoptive parents. It’s hard to believe, after going through so much, that good things really were in store for us. We weren’t going to let the stigma of depression ruin those chances.

My Symptoms

There were many. I began emotionally eating, and I put on a lot of extra weight. After all, didn’t I deserve it, after our long and difficult road to parenthood? And then there was my age: I was in my early 40s—already older than most moms of infants. I may have appeared confident on the outside, but on the inside, I was very insecure about my ability to parent. And, good grief, what would I have in common with the fellow moms on the playground who were half my age?

There were many. I began emotionally eating, and I put on a lot of extra weight. After all, didn’t I deserve it, after our long and difficult road to parenthood? And then there was my age: I was in my early 40s—already older than most moms of infants. I may have appeared confident on the outside, but on the inside, I was very insecure about my ability to parent. And, good grief, what would I have in common with the fellow moms on the playground who were half my age?

Another insecurity was related to “motherhood intuition”—in short, I didn’t seem to have it. I definitely didn’t see parenting as this beautiful and natural inclination that so many people had described to me. “There’s no instruction manual, but you just figure it out and it all just kind of works out,” they said. “You’ll know what to do when the time comes,” they said. But, this was not a credo that I connected with in any way. No, I did NOT know what to do when my son was crying and pushing me away and searching for someone else in the doorway! Why wasn’t I getting it? Was it because I was Matthew’s adoptive mom versus his birth mom?

Other symptoms included exhaustion—it was constant. I had trouble getting out of bed every morning. I had zero energy. My moodiness had reached an all-time high, and my motivation an all-time low.

Another factor was the weather: Two massive snowstorms visited us just weeks after Matthew had come home. These storms literally trapped us indoors for a whole month with a baby who, during crying bouts, we couldn’t comfort by taking a soothing car ride or walking him in the stroller down the streets of our neighborhood. All we could do was walk him, around and around and around the circle that was our living room/kitchen/dining room/foyer—again and again and again and again. We carried him on our back, in a carrier—the way parents do in Korea. It comforted him—the familiar posture, the movement. But, I have to admit, the non-changing scenery made me crazy, and I was climbing the walls, feeling a desperate need to get outside but physically unable to do so. A wall of snow 5 feet high surrounded us. We lost power. The 3 months of maternity leave I had envisioned myself living ended up looking very, very different. We couldn’t take those walks in our little suburban community. It was hard to introduce Matthew to our neighbors or have friends over because of the winter weather and the severe blizzard conditions that lingered.

Infants Grieve, Too

It was during this time that we learned just how powerful the grief of an infant can be.

After a few weeks, Jeff returned to work. I still had 8 weeks to go before resuming my job as an editor at a local nonprofit publisher. Up to the time that Matthew came home to us, I had kept myself busy with my many interests and hobbies. But, now, I spent my days at home alone with my son—and he was grieving.

His grief surprised me. It was overwhelming and confusing. The agency had told us that we should expect signs of grieving—but it’s hard to believe such intense grief can manifest in a human being so young. I learned that infants grieve, too—some more so than others.

I would feel so angry and frustrated with my son when I couldn’t figure out why he was crying. Later, when we finally told our social worker about the bouts of incessant crying, we came to understand that he was intensely physically grieving for his foster mom in Korea. Theirs was a close bond: The photos and notes she packed in his bags made that very clear. When our social worker gently helped us realize this, the guilt hit me like that wall of snow I faced whenever I tried to open our front door. He was just a baby. He had seen many changes in the past few months. He needed love and unconditional patience and a deep presence.

For as emotional as my depression was, Matthew’s grief was physical. During these episodes, I felt an inability to “reach” him and comfort him. It felt like he didn’t want me. He bonded more instantly with my husband than with me. That was hard to face. I expected to be that “chosen one.” Come on, I was the mom! The perfect family bond I had predicted we’d experience was not happening. I was so disappointed.

His grief episodes happened mostly before bedtime, and they were so hard to watch. He’d cry and call out to his foster mother using the Korean word, “Umma” (mother). In those moments, I couldn’t help him. I could hold him, but he’d arch his back and push me away (literally, put his hands on my chest and push). He would toss his head backward and claw at me. He’d then turn his head and look toward the doorway of the room. This is sometimes referred to as “searching behavior”: He turns toward the doorway of whatever room he’s in, looking for someone who previously gave him comfort. Not seeing her, he gets upset and starts crying and can’t be consoled. And the pattern repeats itself.

For more information on grief and how it may manifest in newly adopted infants, check out Is It Grief? Why Challenging Behaviors May Be Signs of Grieving.

I’ve Got This—Wait a Minute, Maybe I Don’t . . .

We called our social worker, who told us there was pretty much nothing we could do but be there, see him through this, and show him that no matter what, we weren’t going anywhere. So, as he cried and cried, we would hold him as best we could as he persistently pushed us away.

And the depression? I pushed it away. There was so much going on—of course, I justified to myself, it was normal to feel sad and weird now and again. New parenthood. New family member. Trying to establish a routine. Trying to understand and deal with our son’s grief. We were just another new family, like any other new family, trying to find our way in the world. I was just a new mom, adjusting. “I’ve got this.”

And then the day came when it hit me: I don’t “got this.” I need help!

What Helped Me? A Book About the Blues!

After finally admitting to myself that something wasn’t right, that maybe I was depressed, I quietly began doing some research. I read some of the post-adoption resources our agency had shared and found a short description of PADS. My quest sharpened. Maybe I was on to something.

The pivotal moment for me was finding Karen J. Foli’s and John R. Thompson’s book, The Post-Adoption Depression Blues: Overcoming the Unforeseen Challenges of Adoption. It took me just 2 days to read it. As I read this book, I realized that I had PADS—and that it was okay. I’d be okay. I wasn’t flawed. I was anything but. I was human. And I deserved to be happy.

The first step in becoming happy again is admitting that you have this thing—naming it, connecting it with yourself. It feels scary at first, but, in reality, there’s also this sort of simultaneous relief. At least, now, you know what you’re dealing with. There are strategies for coping with PADS. There really is a way out of the darkness and into the light—and, for me, what did it was reading a book about the darkness whose existence I had vehemently denied for a long time.

With Foli and Thompson, I had finally found a book that didn’t just sidestep PADS by talking about it only in one tiny little paragraph. The entire book is about PADS and only PADS. It wasn’t an offspring discussion from PPD—it wasn’t buried in a sidenote under the more general category of depression. It was its own topic, worthy of not just an article but a comprehensive book. Written by adoptive parents who are also in the medical field and are scholarly writers and researchers.

It was then that I began dealing with my depression, head-on.

How I Dealt With My Depression

I began meeting with my therapist, together with my husband for couples counseling, to continue dealing with the grief of our miscarriage (which, we discovered, was still present) as well as navigating our new roles as parents—and addressing my depression. In therapy, I bravely began discussing my ambivalent feelings about parenthood and how I didn’t feel like I was quite “getting it” or good at it, at times. I decided to go back on a low-dose antidepressant. That helped more than I liked to admit. I told some close friends that I was having some problems adjusting to life as a new mom (I got over my fear that they wouldn’t understand or would think bad things about me.) I met a new friend for lunch at a local diner—a fellow adoptive mom who had gone through this year earlier. Her kids were older now. She talked me through it, and she really helped me! I unloaded all of my feelings, and she validated them and helped me see that feeling this way didn’t make me a “bad mom.” I resumed doing some of the things I loved to do. I took a healthy cooking course (which was way outside my comfort zone, I might add). I got back into yoga. I read more books. And, now that the weather had finally broken, I began taking those idealistic neighborhood walks with my family that I had so wanted to do in the chill of January when the stubborn mountains of snow and the unplowed roads had other ideas.

Therapy is pretty much an ongoing presence in my life. It grounds me. It helps me in my desire to work on important issues related to self-love and self-care and my desire to be a better person, a better mom, a better wife, and a better friend. I no longer see therapy with that stigma, as if something is “wrong” with me just because I see a psychologist.

If you’re reading this, and you too are suffering in silence, I encourage you to take the brave first step and get help. You’ll be stronger for it. Don’t wait. Do it now. And know that you are not alone.

Back in 2010, I was stuck. I was going through something awful—and I chose to do it almost entirely alone. But then, I opened the door a crack, and I peeked through from the darkness into the light. And I liked what I saw, how I felt. It was a gradual awakening. Opening the door a few inches wider, I went back for more. And more. And still more. That door is now wide open. Hope fills my heart. I am in love with my life. My son and I have THE MOST AMAZING bond. I have had people in the choir, at work, strangers in restaurants, come up to me and say, “Wow, it’s clear that you and your son have such an incredibly close bond!”

At the End of It All, Hope

Now, years later, with PADS in my past and regular therapy in my present, I am still someone who wears her heart right out there on her sleeve. I’m still a happily married mom. That chubby little bundle of the baby from 2009 is now a slim 75-pound, almost-as-tall-as-me third-grade boy. Sushi (not kimchi) is his favorite food. (Go figure.) But he loves himself some mandu, and those Korean seafood pancakes are his fave. He’s a rising karate student (gold belt). He has a mean way with a lightsaber, and he can answer any Star Wars question you throw at him. He’s good at math and reading and likes basketball. He is thin and wiry, and his strong, dark eyes are one of my biggest weaknesses. He’s from South Korea, and he’s proud of it. So are we!

Now, years later, with PADS in my past and regular therapy in my present, I am still someone who wears her heart right out there on her sleeve. I’m still a happily married mom. That chubby little bundle of the baby from 2009 is now a slim 75-pound, almost-as-tall-as-me third-grade boy. Sushi (not kimchi) is his favorite food. (Go figure.) But he loves himself some mandu, and those Korean seafood pancakes are his fave. He’s a rising karate student (gold belt). He has a mean way with a lightsaber, and he can answer any Star Wars question you throw at him. He’s good at math and reading and likes basketball. He is thin and wiry, and his strong, dark eyes are one of my biggest weaknesses. He’s from South Korea, and he’s proud of it. So are we!

But, as his mom, one of my proudest moments came when I was able to overcome post-adoption depression. Because that made me more emotionally available for him, more able to bond with and connect with him. I am now living my life with abundant joy and a confident sense that I am a really, really good mom to my son. I’m certain of that. My story of post-adoption depression has ended, and what I hold in my heart now is an overflowing sense of hope.

For Further Reading

Check out this excellent three-part series on PADS, titled “From Sunset Till Dawn: One Woman’s Passage Through Post-Adoption Depression”:

Part I: When I Began My Adoption Journey, I Had Never Heard of Post-Adoption Depression

Part 2: My Descent Into Post-Adoption Depression Began on Placement Day

Part 3: What I Wish I’d Known About Post-Adoption Depression

Find Help

If you’re ready to seek help, find a professional who you can talk to—preferably someone who has experience working with adoptive parents who have experienced depression. If you’re looking for a less formal solution, and just want to chat with some fellow parents, check out Adoption.com’s thriving and active community of individuals whose lives have been enriched by adoption. Within that community for post-adoption depression, there are several active forums on post-adoption depression. There’s even a Facebook group for parents with PADS. There are so many outlets for support—find the one that works for you.

If you’re ready to seek help, find a professional who you can talk to—preferably someone who has experience working with adoptive parents who have experienced depression. If you’re looking for a less formal solution, and just want to chat with some fellow parents, check out Adoption.com’s thriving and active community of individuals whose lives have been enriched by adoption. Within that community for post-adoption depression, there are several active forums on post-adoption depression. There’s even a Facebook group for parents with PADS. There are so many outlets for support—find the one that works for you.

Are you ready to pursue adoption? Visit Adoption.org or call 1-800-ADOPT-98 to connect with compassionate, nonjudgmental adoption specialists who can help you get started on the journey of a lifetime.