How Infants Grieve | A Guide for New Adoptive Parents

Grief doesn’t discriminate by age, and infants are no exception. Yes, infants do grieve. Some people may find this surprising, but, it’s true. When infants experience traumatic loss (it doesn’t have to be a death, but any kind of loss of the familiar, safe, comfortable), the way they deal with that loss often manifests in the form of grief.

In the case of adoption, that loss usually shows up as a change in not only the caregiving environment but the caregiver him- or herself. Having gotten accustomed to “the familiar” (be it the face of a loving foster parent, the feel of a particular family dynamic, or the physical space of a caregiver’s home), any change in that familiar routine and those familiar faces can cause an infant to experience honest-to-goodness grief. Because infants are pre-verbal and can’t tell us what they are thinking, this grief looks mainly physical and behavioral.

As the mom of a child we adopted from South Korea, I found the fact that infants grieve surprising when I learned about it. Now that I know what I know, I’m surprised that I was surprised! I only half paid attention to the infant grief presentation that our agency gave at one of our waiting parent support group meetings way back when. I thought, “Oh, this isn’t going to relate to MY kid!” But, when my child actually experienced it, that’s when I sat up and really paid attention. I wanted to help him but didn’t know how, and that led to post-adoption depression on my part (see “What Is Post-Adoption Depression?” and “My Journey With Post-Adoption Depression”). So, we talked to our caseworker about what we could do. And, I educated myself on the complex world of infant grief.

Because infants are pre-verbal, their grief is physical or behavioral: They can’t “tell you” what they are experiencing (and even when children are verbal, oftentimes they cannot put into words the fact that they are grieving, per se).

Signs That an Infant Is Grieving

To get some insight into infant grief, what it looks like, we spoke with Child Development Specialist Rebecca Parlakian, M.Ed. Rebecca is Senior Director of Programs at ZERO TO THREE, a DC-based nonprofit that advocates on behalf of babies and toddlers. We asked her, “Can infants really experience grief? What are the signs that they are, indeed, grieving?” Here’s what she had to say.

“Infants can experience grief, particularly when they are grieving a primary caregiver. This comes as a surprise to many adults, but imagine an infant—who is so dependent on caregivers to have their needs met, who is held by a caregiver, gazes into their caregiver’s eyes, and knows this caregiver’s touch as they are fed, diapered, and bathed. This caregiver knows the infant and can provide comfort, reassurance, soothing. When the infant is unable to calm (researchers call this self-regulation), the caregiver uses herself to help the infant calm (through soothing touch, holding, soft words, swaying)—we call this co-regulation, and it’s an important part of early relationship-building. And then, all of a sudden, this caregiver is gone. It is someone else’s face and eyes, someone else’s touch (the feel, the pressure, the approach is all different), the smell of their skin and clothing is different, they hold the infant in different ways, they go about daily routines differently. This new caregiver tries to soothe the baby but hasn’t yet discovered what their shared “recipe” for soothing will be. The infant is distressed and protests the loss of his/her caregiver, maybe irritable/hard to console, may cry more (while some babies may be quieter or “shut down”), may appear to be searching for someone, maybe less responsive/have a “flatter” expression, may seem anxious, and/or maybe less hungry/experience temporary weight loss. With time, an infant will learn that his/her new caregiver will meet his/her needs, love, nurture, and keep him/her safe—just like the previous caregiver did. But this process takes time. The infant needs repeated experiences of a caregiver responding in a timely way to his/her cues, providing consistent comfort and nurturance to trust that this person truly will never abandon him/her and that this relationship will be a “safe home base” for soothing, care, and loving interactions. Over time, these repeated interactions become the basis for a new secure attachment.”

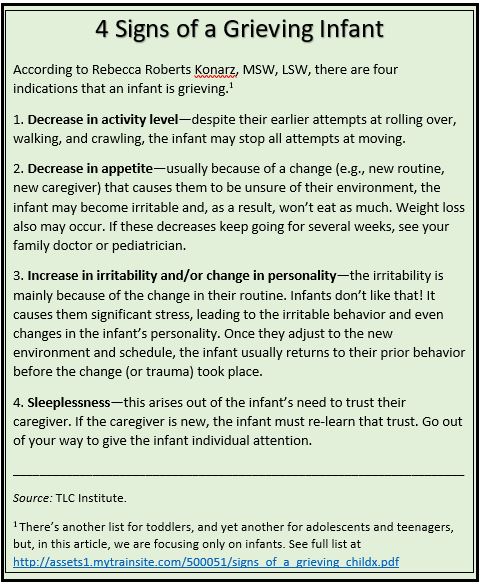

For a quick summary of the signs that an infant is grieving, see the text box on this page titled “4 Signs of a Grieving Infant” (or, see the PDF here).

Do ALL Adopted Children Experience Grief?

Some parents who are reading this might wonder, “Is grief a definite, or a possible? Should I expect that my child will experience this, or does it just depend?”

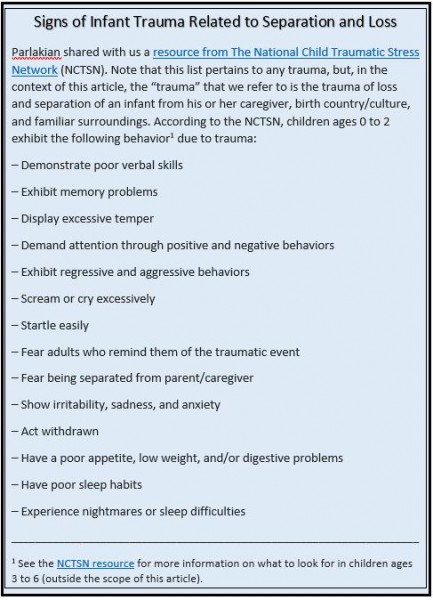

“The grief experience is different based on the life experience of the child,” Parlakian explains. “If the child had a ‘parent’ (e.g., a foster parent) before the adoption, then it is quite natural that this person/relationship is one that the child will grieve—and grieve deeply—if the two of them had established a secure attachment. If the child was cared for in the context of an orphanage without a ‘primary’ caregiver, then it is less likely the child has a particular relationship they are grieving, but [he or she] may show some of the signs above in response to a new setting, country, language, food, and caregivers. This transition can be traumatic (even if it is ultimately positive)—and the signs of trauma are very similar to the signs of grief noted above (see a comprehensive list of traumatic symptoms, and note that for toddlers, typical responses to trauma include regression—a return to earlier behavior like toileting accidents—as well as challenging behavior).”

A Beacon of Hope Through the Haze

Palladian reminds us that in the throes of infant grief there also lies a positive element: HOPE. Hope for yet another loving, secure relationship, the ability on the part of the infant to connect with their new caregiver and/or parent(s). Remember, if the infant formed a secure attachment with their previous caregiver, it means that they have the ability to form a new attachment with someone else (i.e., you)! They just need some time. A prior healthy attachment to a caregiver is a beacon of hope that your child can (and will) connect with you, in time. Palladian encourages us to see this as a positive sign that it is. “If babies have built a strong relationship with a foster parent, that is a great thing! Grief is hard to experience—and hard for an adoptive parent to watch—but it means that the baby has learned what a loving, healthy relationship feels like. Infants can establish a secure attachment to the new caregiver(s) once they have learned that these caregivers are trusted, consistent, and loving.”

Parents whose adopted children are experiencing grief can rest assured that there is hope at the end of all this.

Early Trauma Is Not Destiny: Advice for Parents

Palladian ends our conversation by shining a light on the darkness of grief and sharing an optimistic outlook on the long-term effects of infant grief and early trauma. “Early trauma is not destiny. Parents should know that early traumatic experiences can be buffered (or, overcome partially or wholly) by a child’s consistent, loving, nurturing relationships with their new caregivers.”

What advice does she have for new adoptive parents? First, stay the course; this is a more typical response than you might think! “It is critical that adoptive parents understand that distressed, protesting, and/or challenging responses from babies and young children are typical responses to an overwhelming life event.” Second, she encourages parents to seek help so that they can support their infant—and themselves—in navigating this grief. “It is even more important that adoptive parents receive the support and services they need to provide children with the consistently loving relationships necessary to buffer young children through the transition. This may/should include attending support groups so parents can share their natural feelings of frustration, concern, and worry, as well as sharing progress, helpful strategies, and stories of hope; access a to child development specialist or mental health therapist with experience working with very young children; access to early intervention services; and other supports as needed.”

For more information on infant grief, see the following resources.

- How the Grieving Process Applies to Adoption

- The National Institute for Trauma and Loss in Children

- Infant and Toddler Grief

1 See the NCTSN resource for more information on what to look for in children ages 3 to 6 (outside the scope of this article).